link to slides

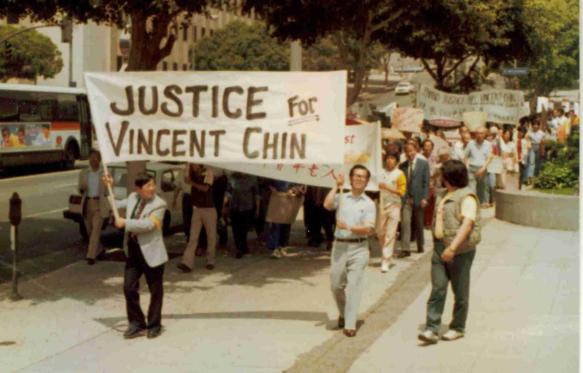

On the surface level, the #TechWontBuildIt movement looks to be a movement focused on organizing engineers to stand up against unethical decisions made by company leadership. And the public is paying attention because the companies involved are big, household names in the tech industry (read: Google, Microsoft, Amazon, etc.). However, at its core, the #TechWontBuildIt movement isn’t just made up of concerned software engineers; The movement sits at the intersection of a variety of older social movements, and the application of powerful software to control vulnerable populations is just the latest area of contention.

A prime example of this cross-movement collaboration is the Immigrant Rights movement. One of the sub-movements I investigate in my research is the #NoTechForICE movement that is specifically focused on pressuring tech companies to cancel their contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement due to the Trump administration’s invasive immigration policies. The Immigrant Rights Movement has long been calling attention to immigration issues, well before Trump took office. I chose Sasha’s book, Out of the Shadows, Into the Streets, because I wanted to read more about the Immigrant Rights movement and better understand the organizing tactics the activists used to build a successful movement.

“A key issue in this often blurred debate is the role of communication technologies in the formation, organization, and development of [social] movements.” — Manuel Castells, Foreward

The book opens with an investigation of the media ecology of the Immigrant Rights movement in the first chapter. English language news channels failed to anticipate the power and scale of the movement and consequently provided spotty coverage. Instead, we saw Spanish language commercial broadcasters providing constant coverage of the movement and playing a crucial role in calling people to action. In addition to mass media, community-driven radio and media, streaming radio, social media also allowed activists to organize and gain public visibility.

In the second chapter, Costanza-Chock defines transmedia organizing as “the creation of a narrative of social transformation across multiple media platforms, involving the movement’s base in participatory media making, and linking attention directly to concrete opportunities for action.” She looks at the 2006 school walkouts as a case study and points to the student-driven organizing effort as an example of how transmedia organizing can engage participants in creating a shared narrative. Students made flyers, communicated and debated over MySpace, chatted over AIM and other chat clients, and taught one another how to transfer videos and photos from mobile devices to computers and upload them to the web.

Next, Costanza-Chock moves to talk about the power of framing and the importance of participatory media in amplifying the voices of protestors on the ground. During a peaceful rally in MacArthur Park (LA), riot police stormed the park and attacked the crowd, which included reporters from mass media outlets. The LAPD reframed the attack as a melee caused by a communication breakdown in the chain of command, and TV news showed the protestors in a negative and/or dehumanizing light by relying on a simplified conflict narrative of violent clashes between police and protestors. In response, activists produced their own media from footage shot by protestors on the ground, creating a true narrative of the events and allowing grassroots voices to be heard in their own words.

In chapter four, the book discusses media practices that were used during the APPO-LA protests in Oaxaca, Mexico to strengthen connections with communities abroad (particularly communities in LA). Activists were spreading media texts across platforms, and most importantly, into offline spaces (video sharing with VCRs and tapes). They took advantage of the fact that a movement can best use digital media when the base group is already familiar with the tools and practices of network culture. This type of media sharing was particularly important for a community that has one of the lowest levels of Internet access among all demographic groups in the US.

Low-wage immigrant workers have less access to media-making tools and skills than most people, so developing digital media literacy is an important goal for many community-based organizations (CBOs). In chapter five, Costanza-Chock calls out a number of CBOs that make a specific effort to increase digital media literacy. The Institute of Popular Education of Southern California and Garment Worker Center have both created popular education workshops around digital media. VozMob takes advantage of the widespread access to mobile phones and publishes a newspaper that can be posted to from mobile phones. These CBOs face challenges such as lack of funding, low training capacity, lack of familiarity with new tools, language barriers, lack of trust, and lack of time and energy to participate.

The sixth chapter investigates the various pathways into participation in social movements for young people, particularly undocumented youth (DREAMers). Some are introduced through participation in other politicized activity (fighting for access to education, fair trade, workers’ rights; mass mobilizations). Others are mentored by seasoned activists or pulled into media production, circulation, and reception. Costanza-Chock points out that participation in media making is a key entry point to further politicization and deeper involvement. Through media making, DREAMers have been able to tell their own stories and develop a strong public narrative.

Transmedia organizing can be incredibly impactful when executed properly. However, with the mainstreaming of transmedia organizing, we have seen well-funded groups create media with little accountability to the movement base. Chapter seven points to such projects, including Define American, a participatory video campaign started by Jose Antonio Vargas, the Dream is Now, a short film created by David Guggenheim and screened at the White House, and FWD.us, a media campaign launched by a group of Silicon Valley executives that uses cutting-edge online organizing tools. Misguided transmedia organizing can often choose poor framing or issue calls to action that miss the mark. In the best case, it means strategic failure. In the worse case, it means negatively impacting the movement’s goals.